By Ashok R. Chandran

Media

IN MARCH 2014, the Poynter Institute of Media Studies, a leading journalism school in the United States, dipped its feet in Indian waters through three workshops, one each in Chennai, Kochi, and Bengaluru. In turn, in each of these three-day collaborative workshops, mid-career Indian journalists and journalism teachers got a taste of contemporary journalism and journalism education in the United States.

The Kochi workshop was organised in partnership with the Kerala Press Academy, and it ran from 23–25 March at the Taj Gateway. To match the pulse of that edition, I am going to shift gears. So, please fasten your seatbelt as we zip through the sessions.

Day 1

Sunday morning. 0845 hrs. Journalists stand in queue near the registration desk. That in itself is ‘breaking news’ material, but goes unreported.

Inauguration at 0900. Participating journalist Sabin Iqbal tweets from the venue ‘#poynterindia workshop in Kochi gets underway. Shanna from US Consulate in Chennai addresses the workshop.’ Welcome to journalism education in the new media era—even while you are in the classroom, you toss a news bite to Twitter. And the faculty have created a hashtag for students’ use!

Inaugural speeches are subbed-like crisp, and within 15 minutes, we are into the business at hand. Howard Finberg, Director at Poynter and ‘leader of the expedition’ to India has kicked off with an introduction to Poynter and the workshop. It is not every day that one gets to see in this part of the world, an energetic 70+ educator enlightening the audience on ‘The Exciting, Changing Future of Journalism’.

We need to rethink the way we report news and train journalists because two forces—technology and economics—disrupt creative industries.

Finberg’s core message is that we need to rethink the way we report news and train journalists because two forces—technology and economics—disrupt creative industries. He draws on the work of Clayton Christensen (The Innovator’s Dilemma) and argues that established firms which undertake incremental improvements remain vulnerable to disruptive innovations. Finberg gives the example of the US print media industry, where in the last 10 years, newspaper advertising revenue fell dramatically, and value was created by freshly minted companies.

While disruptive innovations take place in industry, there is no consensus yet on what shape journalism education should take. Presenting results from The Future of Journalism Education 2013 report, which he co-ordinated, Finberg shows that there is a wide gap between what professionals value and what journalism faculty value. For example, while nearly 98 per cent of educators surveyed felt that a journalism degree was very important or extremely important in the ability to gather news, only about 59 per cent of journalists felt so. Finberg rounds up his session with a sneak peek into the Core Skills for the Future of Journalism report (released April 2014), which he co-authored, and which too reveals a disconnect between educators and professionals. He ends with an exhortation to be open to change and adapt.

Barely has Finberg sat down when Tom Huang launches into ‘Credibility and Journalism in the Digital Age’. Wiry and bespectacled, Huang is the editor of the Dallas Morning News, and he comes across as a calm, methodical man who will give you a prize if you make him smile. Slowly and softly, weighing every word, he explains the three pillars of credibility—seek truth, act independently, and minimise harm—which are guiding principles in the code of ethics of the Society of Professional Journalists in the United States.

He then brings up a case study. On the big screen, a multimedia story comes alive, at the end of which, the audience is invited to reflect on the story and examine how faithful it is to the three cardinal principles. ‘Yolanda’s Crossing’ is about a Mexican girl raped by her uncle, and was published in Huang’s paper in 2006. Now, thousands of miles away, and seven years later, Indian journalists dissect the reportage and voice their opinions in a discussion (‘more lively than the one in Chennai’, observes one faculty); it helps that Huang is a man of few words and adopts a genuinely participatory approach. We have not even reached the first tea break, and Poynter’s pedagogy is winning over Indian journalists.

Of the three workshops, the Kochi edition has attracted the most number of applicants and boasts of the most acceptances, but the turnout is only marginally higher than at Chennai. Only 75–80 of the 120 expected delegates have turned up. So, there are more than enough snacks to go around. The long queue at the loo is because the air-conditioner was set at 17 degrees Celsius.

Next up is Casey Frechette, who teaches at Poynter and leads the session here on ‘Digital Tools and Technology in the Newsroom’. Frechette has to hurry up to cover 59 slides; he wisely skips some of the initial theory-sounding bits and goes for the tasty bites. He pitches the expanding digital skill-set that is now required (such as writing for the Web, working with plugins and APIs, making games, developing for mobile, and managing social media); some of these are entirely new to some participants, and digital jargon is enough reason to relax and remain indifferent. Frechette then talks about US newsroom hiring and the recruiters’ ads for data journalists, news app developers, engagement editors, and interactive producers. What?! Unfamiliar designations! This is too close for comfort. The bouncer hits even the veterans in the jaw.

Is Frechette floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee? Nah! He says, ‘All journalists need to be digital’, puts on his friend-next-door smile, and takes us through five digital trends—short-form video, news games, open data, mobile content, and sharing the work. About each of these trends, he lists the advantages, introduces the tools to make it happen, and gives examples from real-world journalism (like the recent ‘Travoltify Your Name’).

Occasionally, Frechette tosses a question to the audience for discussion. Once, when a participant asks a question about feature writing, Frechette invites a colleague (who has more experience in the genre) to answer it. The non-hierarchical approach to training is an eye-opener. Collaborative teaching delivers maximum value to students. By the time Frechette winds up his session, the audience has warmed up to the digital era. The room temperature too has been raised to a tolerable 20.

When compared to the food for thought offered, the lunch is spartan.

For the post-pulao session on ‘Better Story Ideas and Reporting’, Tom Huang is back in the saddle, and he offers three keys to better stories: brainstorming, planning (big stories), and coaching. Through a brainstorming exercise, he proves again his excellence in participatory education. On planning complex stories, he shares his experience in preparing for the 50th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination (a big story for his Dallas paper).

Coaching is uncommon in India, but will probably develop in the coming years. Put simply, it refers to editors engaging in a series of conversations with reporters, to help the reporter gain focus and organise the story, especially in long-duration projects. Huang advises, ‘Instead of fixing things at the end, you coach or guide the reporter as the story is being written’, and offers practical tips, such as short outlining, mapping, and visualising.

The blast is reserved for the last. The Indian face of the Poynter team looks so Indian that it is difficult to guess which part of the country she belongs to (and she is proud of it). Vidisha Priyanka, it turns out, is originally from Bihar; and what follows is close to a Gangs of Wasseypur on multimedia journalism.

It begins with some raw and violent assertions about digital journalism (viewers expect clean audio in broadcast journalism but not in digital; if you are transparent, your viewers are more forgiving of spelling mistakes unlike in print journalism). She narrates how a story progresses in digital during the day, from the time a tiny bit of information reaches the newsroom—a brief article quickly appears, an image gets added in a while, followed by a video clip from the reporter’s mobile phone, plus fresh infographics, and so on. She suggests keeping a checklist handy and planning stories, so that one can quickly use sound, visuals, and action supported by different elements (like map, mashup, animation, or infographics). The discussion is punctuated with pistol-like shots of online tools useful for producing the different types of content. As if to demonstrate that digital journalism is in a hurry, she suddenly whips out a machine gun and rattles off online tools (from the familiar Google Maps and Storify, through mashups and Meograph, to Dipity, Ustream, and Videolicious).

All through the session, the female Rambo speaks clearly, answers queries from workshop participants, and seems determined to produce a few digital journalists by the end of the mission. Finberg takes a photo and tweets ‘@vidisha71 owns the room talking about multimedia at #PoynterIndia workshop. Lots of teaching.’ At least one middle-aged print journalist must have been killed that afternoon and reborn as a youthful digital warrior.

Day 2

The nine o’clock session begins 20 minutes late. Where the wheel of time has been turning for 5,000 years, what is 20 minutes? Sadly, appreciating Indian spirituality is not on the Americans’ agenda that morning.

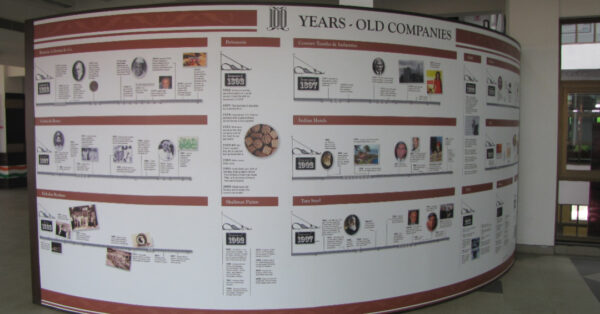

The first session is on the business side of journalism, and the speaker is Zella Bracy, who works on the business side for the McClatchy Company. Picture a female incarnation of Mogambo with the stock line, ‘It’s-aaaaaawl- about-the-money’. Later in the day, she would reveal her deadly approach to journalism, but for now, she systematically shows the financial trajectory of the print media industry in the US. One of her initial slides makes you sit up—there is a precipitous fall in classified revenue in 2008. ‘Poof! Five billion dollars of classified revenue vanished’, she says with characteristic drama. From then onward till 2013, how the financial and other indicators changed year by year, is what her talk is largely about. Content consumption grew on the internet, classified advertising shifted to online spaces, Americans began reading news on mobile devices, newspapers went bankrupt, and so on. One of her slides tells us that in 2012, the size of the newspaper industry dipped below 40,000 full-time professionals for the first time since 1978.

Bracy also highlights how the newspapers responded to this tsunami caused by recession and technological changes. Each year lessons were learnt, be it the need to monetise traffic, the need to work with technology than fight it, or the growing importance of social media. The picture one gets is of a dynamic industry that closely watches its performance and customer habits (‘data is king’) and responds creatively by experimenting with paywalls, digital ad sales networks, digital marketing agencies, e-commerce, and so on.

Strong leadership is key to transforming the newsroom.

Perhaps to counterbalance the gloom and doom statistics, the following session is optimistic and grandly titled ‘Transformational Newsrooms’. To Jeffry Couch, the editor of the Belleville News-Democrat newspaper in southern Illinois, the big picture is clear: strong leadership is key to transforming the newsroom. With a can-do spirit (a trait one notices in all faculty from Poynter), he then dives into the various practical steps one can take to shift from a print-only newsroom to an integrated, print + digital one. Like his name, Couch presents in a relaxed manner—in contrast to the high-energy, gangster teaching of the previous afternoon—but succeeds in motivating the audience towards public service journalism. Narrating the US experience, he advises us to use consumer data, communicate data and ideas regularly with the staff, be patient and relentless, and (perhaps most important for Indian newsrooms today) eliminate the wall between digital and print staff. ‘All journalists should have digital and print responsibilities’, he believes.

The workshop is fully sponsored through a grant by the US Consulate. The participants, however, must remain satisfied with a green badge emblazoned ‘Poynter Alum’ and a certificate; the ‘CIA’ tag might come later as a bonus, from journalists who missed the workshop.

On seeing the title slide (‘Editorial–Business Collaboration’) displayed in advance on the giant screen, a local journalist asks, ‘Shouldn’t we Indians be teaching them this, since we are miles ahead with paid news?’ The crowd around him shares the cynicism and laughs.

Tom Huang begins the post-lunch session with the key message, ‘Newsrooms must move beyond the traditional firewall between the business side and editorial to generate revenue while maintaining ethical boundaries and building credibility.’ As he and Bracy push for editorial–business collaboration, they run up against Indian journalists (what a strange sight!), among whom the murmurs of dissent have by now rolled into thunderclaps.

A faculty tweets to the world, ‘Heated debate on whether news/business side can work together without crossing ethical lines #PoynterIndia.’ From across the seas, a journalist for the Dallas News (the paper Huang edits) warns: ‘Watch out that @tomthuang is a pit bull.’ Too late! Once you descend, the aerially green Kerala gives way to a soil red in colour.

The faculty see a storm coming but apparently misread it as part of century-long rivalry between journalists and marketers in media houses. So, on the flip charts, when Indian journalists put ‘money’ and ‘compromise’ under the ‘bad’ category, the visiting faculty try to correct that notion. The participatory style that Huang deploys here again, comes to Indians’ rescue. They describe the phenomenon of paid news in the country (apparently unheard of by the Americans) and draw attention to what the Times of India’s Vineet Jain told the New Yorker: ‘We are not in the newspaper business, we are in the advertising business.’ Huang appears tamed.

And thereafter with many of the techniques offered by Huang and Bracy, such as advertorials and event marketing, being familiar to the participants, the session turns bi-directional. Indians speak from experience about the pitfalls of editorial–business ‘collaboration’ while the faculty emphasise ways to maintain a higher standard of ethics. The session is sealed with a Gandhian compromise—there must be collaboration for need, but not for greed.

When one learns so much in a day, it can be tiring (like reading this article). Time for a tea break, with cookies, fried Indian snacks, tea, and coffee on the table.

The final session of the day is on ‘Preparing Journalists for the Future’ by Sue Burzynski Bullard, who teaches at the University of Nebraska and is a former managing editor of the Detroit News. The highlight of her talk is the innovative way in which she uses Twitter while teaching journalism students. Writing tight, headline-writing, and lead-writing can be taught by assigning students to cover live events, she points out. Similarly, students can learn to find the focus of a story by interviewing each other and then attempting to summarise in a tweet. Ethical attribution, use of quotes, importance of verification, gathering information—anything seems possible and good on Twitter. Illustrating with examples, she drives home the message that digital tools reinforce traditional journalism skills.

Day 3

Jeffry Couch, true to form, takes a well-rounded session on watchdog journalism. Initially, along with the participants, he discusses why watchdog journalism is important to news organisations. Couch believes in creating a ‘watchdog culture’ in the newsroom, and he shares dozens of actionable tips, including mining public records, learning public record laws, training reporters in data analysis for database journalism, adding watchdog elements to routine daily coverage, creating a resource guide, involving readers in news-hunting, and pairing seasoned investigative reporters with inexperienced reporters. One of Couch’s strengths is the leadership wisdom he brings to the workshop. Here are three nuggets: ‘Hire people who have a watchdog bent’, ‘Make sure you give reporters and editors the time and encouragement to do watchdog work’, and ‘Be open to where the facts take you’.

Casey Frechette returns with a session on ‘Teaching (and Learning) New Digital Tools’. The new media landscape is full of unfamiliar or unintelligible acronyms (CSS, PHP, JSON, SQL, for starters). What should journalists know? Should journalism students be taught everything? Frechette does a remarkable job of mapping the terrain for journalists and educators. He delineates three zones: production skills (creating and editing audio, video, photos and graphics), coding skills (frontend [user interface], backend [server], data, content management), and connecting skills (social media and analytics). He then identifies four levels of learning (awareness, knowledge, basic skills, and advanced skills). Using these two axes, he outlines the contours of a digital journalism curriculum. Frechette also gives a lot of specific tips on how to teach digital tools in the classroom and encourages j-schools to specialise in a few areas of their choice.

African Daisies—white, pink, and yellow—are at the centre of each table. Between them and the participants, are fried Kerala snacks on a white plate. Most attendees are from the home state. But there are also a few from afar, including Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Pondicherry. As the snacks are crunched guiltlessly, questions fly: ‘Where can I get good banana chips to take home?’ and (pointing to sarkkara upperi) ‘Tell me, how are these made?’ Once, as I fumble for an answer, an exasperated Gauri Vij exclaims, ‘Men!’ Camaraderie blooms when the chips are down.

Sue Burzynski Bullard’s session on ‘Ethics in the Digital Age’ happens next. She discusses ethical lapses, such as plagiarism, fabrication of quotes, and fake photos, and illustrates how citizens are affected when journalists race to sensationalise without verifying (‘Bag Men: Feds seek these two pictured at Boston Marathon’ screamed a headline in a hurry). The class discusses some of the digital age challenges, including copyright. ‘Data journalism can lead to loss of privacy’, she explains with the example of a New York paper which published a map of gun owners after a school shooting. Does it make the gun owners and their neighbourhoods more secure or less secure? Her various examples have the audience in splits one moment and introspecting the next. She winds up by recommending books and online materials to dig into.

Outside the hall, the participants pose with the faculty for a group photo. It is a Poynter tradition, says Howard Finberg. Inside, printed certificates of participation are ready, and the participants pick them up on the way in.

Universal themes resonate with readers.

The workshop climaxes with ‘Finding Focus’ by Tom Huang, who begins by saying, ‘We often know what the news is in a story. We don’t always ask, “What is this story truly about?”’ Using the example of the movie Titanic, the class then plunges into finding the themes in the story. Love? Rich and poor? Man’s hubris? Unlike the ship, though, the class surfaces back, with creativity and laughter, as Huang leads a couple of lively exercises to find universal themes that resonate with readers. He points out that finding the focus can help to determine how one starts and ends the story.

It is time for touchdown and Howard Finberg, who had piloted the workshop into orbit on day one, is called in to bring us back to earth. As he seeks feedback from the participants, I expect the crowd to be tired at the end of three days of non-stop learning, and merely make a few polite noises. The scene is anything but. The energy and enthusiasm of the faculty seem to have infected the audience, as participants cannot stop gushing about their Poynter experience in Kochi. From almost every table in the room, hands are raised, and voices compete to express admiration. Those offering feedback are surrounded by several digital eyes—cameras on mobile phones and iPads. It ain’t sufficient to listen to feedback these days. Audio is passe; video rules.

Weaving his way through the audience, a thrilled Finberg is closely followed by Varun Ramesh armed with Canon 7D. He has been recording sessions and interviewing faculty, with plans to release on Youtube his video of the Poynter workshop. The future is in digital, and the Malayali journalist is already there.

Extra

Correction: The original article in print misspelled Tom Huang’s name more than once. The error is regretted.

Media is a bilingual monthly magazine of the Kerala Press Academy (now renamed Kerala Media Academy)

Credits: Photo originally published in Media (May 2014). Photographer unknown.