By Ashok R. Chandran

Business Standard (New Delhi)

GENERATIONS OF INDIANS have grown up hearing the story of the Indian athlete who looked back and lost a medal on the world stage. But now, in the global economic race, IIM Kozhikode is encouraging us to look back.

As you drive past the IIM-K gate, wind up the hill, and ascend the stairs to the first museum of Indian business history, your expectations rise with every step. Once inside, the initial whiff is of patronage and hierarchy: there are laudatory messages from the President of India and the Chief Minister of Kerala. Past those odd poster-people for Indian business, the adventure picks up.

The first eye-catcher is a mural depicting the local ruler of Kozhikode and the spice traders, including Vasco da Gama, who landed near Kozhikode in 1498. After thus linking local history with the global economy, the museum shifts gears to the traditional narrative of national history. You start at the Ancient pavilion, marked by a giant panel punctuated with backlit prints on glass, that talk of early pottery, urbanisation, and the crafts. The subsequent flow of poster panels is broken by replicas of clay tablets from the Indus Valley, and a model of an ancient bullock cart.

Then on to Medieval, largely a series of vinyl-printed poster panels on economic and policy topics like currency, agriculture, transport, and land revenue assessment. Much the same for Colonial India, Pre-Independence India, and Post-Independence India. In the Business Sectors pavilion, the monotony is offset by the ‘Retail’ cutout installation, a six-letter wall (R-E-T-A-I-L) depicting the evolution of retail trade from kirana shops to malls. In the pond of poster panels that is the Individual Contributors pavilion sit the highlight: two pens and a table-clock that belonged to the late marketing guru C. K. Prahalad. The next two pavilions, Public Sector and Makers of Modern India, are bland.

Wondering where the storyline is headed? Cheer up, the payoff is in the Banking pavilion: memorabilia of the State Bank of India bicentennial (stamps, first-day cover and, believe it or not, a Rs 100 coin), a map of business communities (Chettis, Marwaris, Jains, Vaishyas and others), and specimen notes of Rs 5,000 and Rs 10,000. The oldest exhibits are on display here: an original treasury bill of 1859 and a promissory note from 1881.

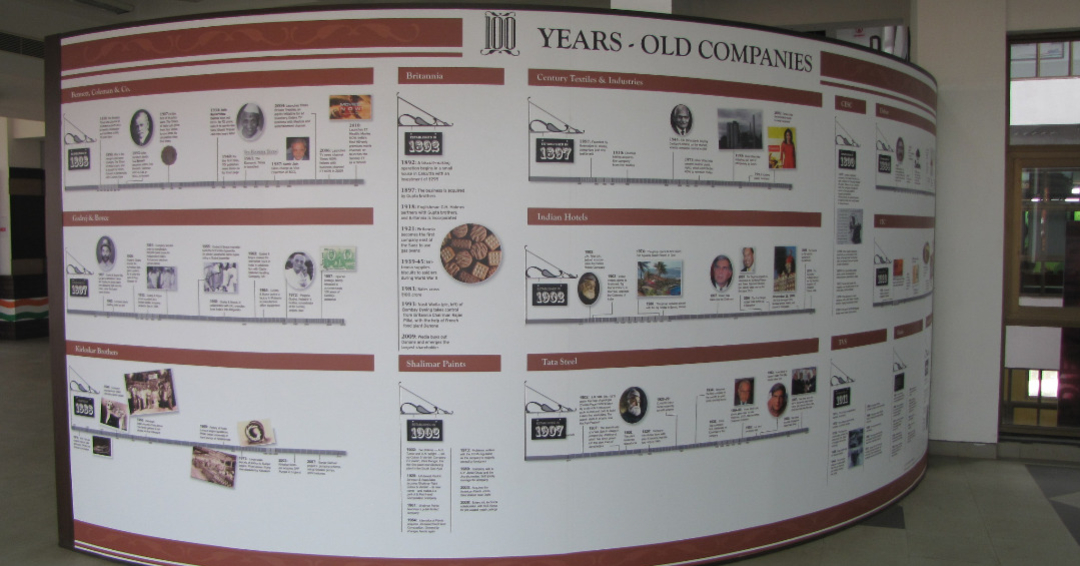

The tale winds down through India Incorporated, which welcomes you with a semi-circular wall chronicling the milestones of India’s 100-year-old companies.

The tale winds down through India Incorporated, which welcomes you with a semi-circular wall chronicling the milestones of India’s 100-year-old companies. In this pavilion, each business group also gets 100–300 sq ft to share its heritage. Godrej does well here. (Did you know that this company, whose locks you use, also manufactured 900,000 ballot boxes for free India’s first general election?) When asked why they did not go beyond static info-photo bricks, Godrej archivist Vrunda Pathare said, ‘We plan to refresh our space yearly once the Museum is fully functional. In stages, we will add audio-visual, facsimile of documents and other such interesting materials.’ The Tatas, Ambanis and Infosys, too, are here, but where are the Birlas and Wipro? M. G. Sreekumar, the dynamic convenor of the Museum project, says, ‘We are hopeful of more business houses and institutions setting up their pavilions as well as sharing their historical collections, artifacts and documents.’ His team has written to at least 600 organisations already. The Reserve Bank of India and the Indian Space Research Organisation are on their way.

Before exiting, stop at the Idea Wall. Your feedback note, written with a marker pen, is instantly digitised and displayed on a nearby screen, and saved for the Museum’s use.

Overall, the 200-odd poster panels in English — most of them enclosed in toughened glass and placed under spotlights — are elegant, but too many. The handful of 3D models and murals are supplemented by 13 LCD screens that display short videos, and eight wall-mounted touchscreens that invite you to flip through photographs and documents. Still, spread over two floors, 13 sections and 20,000 sq ft, the Museum could do with more multimedia interactive zones. ‘Laser show and motion simulator are coming soon’, the authorities promise. To the wishlist, I would add a few sofas in-between to rest tired legs, and a museum shop at the exit.

What lies behind the Indian Business Museum? Debashis Chatterjee, IIM-K’s director, recalls that, ‘In November 2010, when Sanjeev Bikhchandani [founder of Naukri.com] visited us, he sounded the idea of the business history museum of India. IIM-K, too, wanted to inspire business students to turn entrepreneurs. Doing business is in our DNA, yet our [management] ideas are borrowed mostly from the West. Before we can grow wings, we must grow our roots.’

Rather than immediately inflicting a business history course on the MBA students, a museum was conceived to help youngsters learn business history, and develop pride in the country’s past. Its chosen theme was ‘influential India in global business’. In the atrium, a model of a Beypore dhow (a wooden sailing vessel popular among Arab commercial seafarers and built traditionally on the outskirts of Kozhikode) reinforces the thought that ideas and crafts set sail from India.

With a mission to inspire students to turn entrepreneurs, no wonder the Museum presents business history through heroes, leaders and corporate giants.

With a mission to inspire students to turn entrepreneurs, no wonder the Museum presents business history through heroes, leaders and corporate giants. Like the old-style National Council of Educational Research and Teaching (NCERT) school textbooks used for nation-building, the Museum relies on the history-as-fact approach and deploys text-heavy information bundles, even in the interactive kiosks. Maybe one day it will provide space for history-as-interpretation, too, as well as bring alive the buzz of the informal economy, small business, and trade unions. When I tap Mathias Imbach for suggestions, this visiting researcher of business strategy from Switzerland says, ‘Ideas like jugaad can be showcased.’

The chronological approach, executed by Bangalore-based FI Design and Development, helps visitors relate to knowledge acquired in school. But the storyline warrants deeper thought. It now takes India’s conventional template of history (ancient, medieval, modern), adds a thin layer of political history to the modern period (colonial, pre-independence, post-independence), and fills all these with information about the economy. The Colonial exhibits, for example, follow a political path (Portuguese, Dutch, British, French), rather than an economic one (mercantilism, free trade, finance capitalism), thus shying away from challenging the visitor to re-order his or her worldview. And after a point, the story diverges into a miscellany (business sectors, individual contributors, public sector, makers of modern India, banking, home-grown groups). In this masala mosaic, we can taste various ingredients of business, but the thematic flavour gets lost among the chips.

My young guide points out how the museum makes use of the generous natural light the campus gets. Archivist Sanghamitra Sen feels that ‘there is adequate visibility, but the emphasis on natural light fails to create drama’, such as by spotlighting particular items.

The Museum is integrated with IIM-K, draws on the Institute’s staff and amenities, and the working hours coincide. Such insularity can be limiting — for instance, weekends are holidays for the Institute — and the IIMs have a streak of elitism. The good news is that, although the Museum is yet to be inaugurated officially, it is open to visitors. We need more such unconventional decisions from IIM-K, to reach the widest audience.

Dwijendra Tripathi, the doyen of Indian business historians, who had once planned a business history museum at IIM-Ahmedabad, advises IIM-K to ‘develop the museum as a centre for conferences, seminars, colloquia, lectures and discussions focusing on the business history of India. If that happens, the Museum would not be only a repository of material, but a dynamic agency promoting interest in the collection.’ In this early stage, faced with hesitant donors, limited original artifacts, and the absence of a professional curator, the Museum is a few good miles away from fulfilling a vision outlining a serious intellectual approach to business history. But that is indeed the way forward. Is it not sad that even when a premier Institute pumps in over Rs 1 crore, our poor sense of history holds us back?

The Indian Business Museum at Kozhikode is a pioneering initiative, and an important step on the way to helping us understand and appreciate the history of business in India. One hopes that even as the Museum inspires entrepreneurs, cultivates pride in India’s past, and develops into a hub for conversations, it will capture business history in richer ways and thus influence the globalisation of Indian thought. The race is still on.

Extra

This article at the Business Standard website

Copyright © 2012 Business Standard