By Ashok R. Chandran

EVERY OCTOBER, thousands of school children in Kerala, enthusiastically participate in an exam. They know the questions in advance and do not have to memorise facts. They can seek the help of people, periodicals, books, the Web, and their own imagination. The P. T. Bhaskara Panicker Memorial Science Exam for Children is an exam with a difference—a candidate found referring books or asking around gets more marks.

The exam is perhaps unique in India’s educational landscape for three reasons: its aims, content, and organisation. ‘Our objective is to encourage the spirit of inquiry. And develop self-study skills’, says school-teacher V. R. V. Ezhome, key organiser and leader of the Kannur-based Social Action group for Science, Technology and Humanity in Rural Areas (Sasthra).

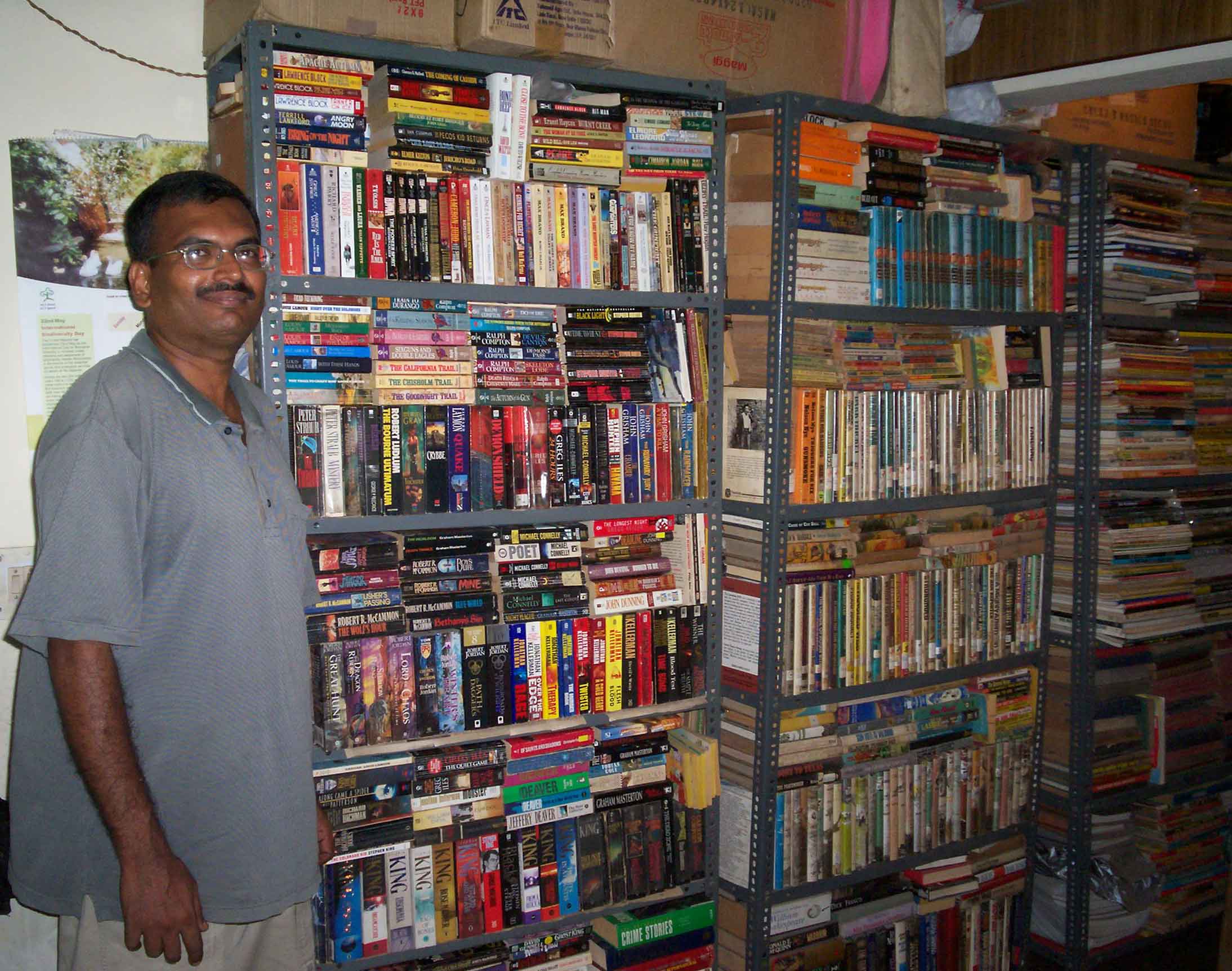

In 1989, dissatisfied with the education system that emphasised learning by rote, Sasthra started summer schools in rural Kannur and neighbouring districts, where children attended classes on poetry, painting, music, mathematics, and grammar. The Science Exam was initially held to develop the habits of reading and library-use among these children. Behind Sasthra, summer schools, and the Science Exam was one man—P. T. Bhaskara Panicker.

PTB, doyen of Kerala’s science literacy movement and a sought-after editor of encyclopaediae, set the first question paper. He also enlisted the support of voluntary associations in central and southern Kerala to organise the exam in their regions. Panicker died in 1997, and since then the exam bears his name.

I have before me the question paper of the 2002 exam. ‘Instructions and Guidelines’ recognises that some questions can be answered in one word, but cautions: ‘that is not what is expected. To answer each question, you must collect as much information, pictures, statistics, etc. as you can.’ Thus, when quizzed about the first Lok Sabha Speaker, a student has to not just name him, but write a few lines about G .V. Mavlankar.

I rush past questions that one finds in other general knowledge tests—quizzes, mental ability, tell-me-why—and stop at Question 68. It asks: ‘Are astrological predictions credible? Investigate based on the predictions for a particular star-sign, as appearing in periodicals of the past five weeks.’ The next touches a contemporary issue—Government policy to shut ‘uneconomic’ schools—and requires the student to write a letter (to the Education Minister) suggesting steps to prevent schools from turning uneconomic. The final question invites the student to write a poem or paint a picture on ‘Gujarat’s Grief’.

Students get marks for citing their information sources. Below one answer, a notebook proclaims, ‘source: sister’. Yearbooks and encyclopaediae are popular reference points. ‘Students call booksellers and newspaper offices to get elusive answers’, informs P. Sudhakaran, coordinator in Ernakulam District. After the competition, there is a scramble by children to get their notebooks back. Who would not treasure the first little encyclopaedia he compiled?

Sudharman, whose daughter ‘took the initiative’ and won a prize, feels that the exam is different, but not better than conventional ones. ‘It is not a test of the student’s ability because he can ask around’, he points out. Joy, another parent, disagrees. ‘The questions are of a high standard. The exercise will be useful to students in the long run’, he believes.

Like the exam, its organisation too is unconventional.

Like the exam, its organisation is also unconventional. The question paper is set by Sasthra and delivered to schools through a network of voluntary groups working on education and related themes. These organisations—like KERDA in Alappuzha, Asha in Thrissur, Seva Mandir in Kozhikode, Aarshabharat in Wayanad—coordinate activities at the district level.

Students have one month to explore and submit answers in notebooks. Evaluation is done by a teacher of that school, or where teachers are less willing, by college students, bank officials, and other volunteers. In each school, two students are awarded prizes, and to reduce bias, one person assesses all the answer-scripts of a particular school. District winners compete at the State level for a gold medal given by the Parassinikkadavu temple in Kannur.

Flexibility in using local resources generates variations in the conduct of the exam. In Thiruvananthapuram, the competition is for high-school students, while in other districts, upper primary students also participate. In Ernakulam District, the exam culminates in a science festival for children. There is no exam fee, but in northern Kerala Rs 5 is sometimes collected to meet costs. Local firms, banks, and shops sponsor events, and members of the public chip in. ‘A restaurant-owner provided food, free of charge, to all students attending the State meet’, recalls a volunteer. Aware of the organisers’ financial constraints, volunteers also put in money to meet local expenses.

The PTB Memorial exam challenges the perception that most schools, especially rural schools, cannot promote explorations beyond prescribed textbooks. ‘In Thiruvananthapuram, the response is greater from rural schools’, observes organiser P. R. Jayapalan of Balavihar. Participants belong to diverse socio-economic backgrounds, and among recent prize-winners was the daughter of a plantation labourer.

Those familiar with P. T. Bhaskara Panicker and his work will agree that the annual exam is characteristic of the man who conceptualised it. Like PTB’s breadth of knowledge, the exam covers a wide range of topics—including current affairs, science, geography, history, culture, and agriculture. For implementing innovative ideas, PTB mobilised large numbers of organisers and participants. In Ernakulam, one of the ten districts where the exam is at present held, efforts of Spark Research Centre, PTB Smaraka Balasastra Pareeksha Samithi, Sasthra, and Samanvaya attracted 75,000 students from 346 schools last year.

In many ways, the PTB Memorial Science Exam for Children is a beacon for our times. It is an extraordinary effort involving students, teachers, parents, socially-conscious organisations, and public-spirited individuals. It supplements conventional tests and fills a gap in our education system. In the wider public sphere, without relying on high-voltage public relations or management jargon, it displays the power of civil society to intervene constructively. P. T. Bhaskara Panicker demonstrated it in 1990. Dozens of volunteers he inspired do it year after year.

EXTRA

Original article and Website version Copyright © 2003 Ashok R. Chandran. Published version Copyright © 2003 The Hindu. ‘Spirit of Inquiry’, 8 March 2003, Quest supplement, The Hindu (Thiruvananthapuram edition) http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/quest/200303/stories/2003030800380100.htm.