By Ashok R. Chandran

The Hindu Business Line (Chennai)

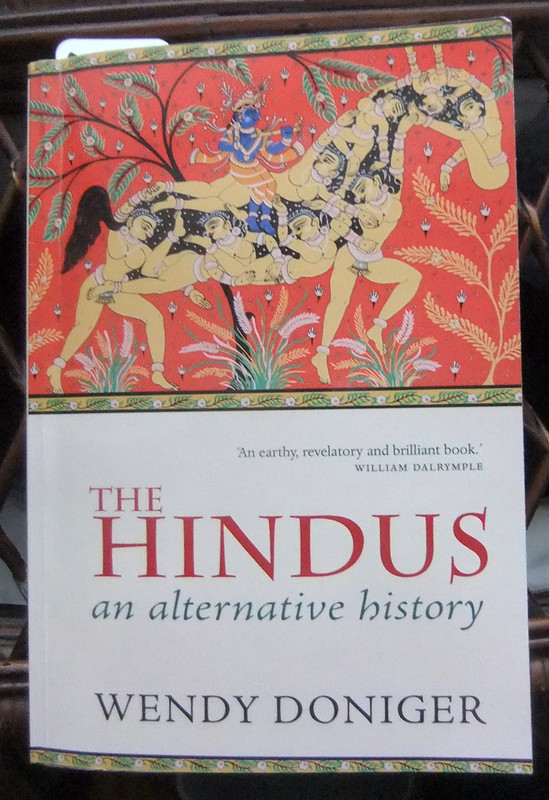

EVER SINCE NEWS broke of Penguin India’s agreement to withdraw The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger, writers, academics and readers have been crying foul and shooting the publisher. This reflexive round has succeeded in catapulting the issue of free speech to primetime news and page one. But continuing to target Penguin is unfair and undesirable.

In the battle for expanding free speech, it is now time for a round of review and reflection.

On rewinding the tape, we see that the publisher has been neither saint nor sinner. Penguin erred in publishing the Indian edition, but the vociferous criticism has been of its withdrawal.

The first argument is that the publisher should have waited for the court order and, if necessary, appealed to the higher courts. Indeed, if the author or publisher felt the book was legal, they should have done just that.

But what if they felt the book was illegal, which is what they seem to imply when blaming Section 295A of the Indian Penal Code?

When people say, ‘The book might be legal. How did Penguin conclude it was illegal?’ they ignore the everyday publishing environment in which acquisitions editors routinely reject manuscripts they believe are illegal; they do not wait for court orders.

But just as officials take bribes in the hope that they will not get caught, editors occasionally cross the line and publish what they know to be illegal. Recall Doniger’s recent statement: ‘Penguin India took this book on knowing that it would stir anger in the Hindutva ranks.’

It thus appears that the publisher felt the book would offend the religious beliefs of a section of Hindus, and still published it, thereby arguably violating the letter of the law.

True, Penguin’s assessment is subjective. Another publisher who feels the book does not offend religious feelings can publish The Hindus and, if challenged, take the matter to the Supreme Court because legal battles are fought between parties who dispute whether a book is legal, not between those who agree that a book is illegal.

That is why, strange as it sounds, Penguin was right in withdrawing the Indian edition, but wrong in publishing it.

Through a private settlement ahead of a court order, Penguin saved the book, at least temporarily.

The second argument against Penguin is that it killed the book with a private settlement. The leaked document, in fact, suggests the opposite. It only says that Penguin will refrain from distributing or publishing the book in India.

In the publishing world, generally, this means the door is open for another publisher to publish and sell in India by procuring the licence to publish from the copyright owner.

Since Doniger (not Penguin) holds the book’s copyright, anybody who now believes that The Hindus is legal in India would be free to publish an Indian edition of the book after getting the author’s permission.

That window of opportunity would have been unavailable if a court had ruled that the book violated Section 295A or some other legal provision.

Thus, through a private settlement ahead of a court order, Penguin saved the book, at least temporarily.

This being the situation, is there really any justification for theatrics? The High Priestess of Hyperbole asked: ‘Must we now write only pro-Hindutva books?’, as if Section 295A allows books insulting Christianity and Islam, and Penguin bowed to Hindutva.

Elsewhere, a nine-page legal notice was drafted asking Penguin to convert the book to open general license; instead, a one-minute glance at the book would have revealed that the copyright is owned by Wendy Doniger, not Penguin.

Clearly, such rhetoric is silly. Yesterday, it was important to stand up and shout; today, it is important to sit down and think.

Once we stop firing indiscriminately at Penguin, we can divert our energies to thoughtful and constructive action.

The online petition led by academic Ananya Vajpeyi took a step forward by calling for reform of Indian law on freedom of expression, especially Sections 153A and 295A of the Indian Penal Code.

We must build on that and make this a campaign, like the ones for the right to information and the right to food.

Sustained, dedicated and informed action is required to enlarge the space for free expression in India. It must bring together those who share a common interest in writing and reading about religion: writers, publishers and readers.

Our interests conflict at times and cannot be perfectly resolved within the economic and cultural worlds in which we operate. But there is room for manoeuvre. It is possible to find areas of common interest and avenues for joint activities.

For example, writers and publishers have a shared interest in raising their own knowledge of the law relating to freedom of expression. Without greater legal awareness, a rapid descent into self-censorship is likely, and the existing ground for free expression will shrink.

The fight against religious fundamentalism cannot be won by incompetence or ignorance.

Similarly, the campaign’s multi-disciplinary team can offer legal expertise and other resources to publishers, especially small and independent publishers, for whom the size of the fight is usually bigger.

For each book challenged under Section 295A, the campaign can help to set up a fund that finances the legal battle.

The campaign itself would attract funding by publishers who can tap its expertise and resources in future court battles. Penguin, which claimed that Section 295A was ‘an issue of great significance’, can be asked to donate first.

Efforts like these would not only raise awareness regarding the cause but also be barometers of society’s commitment to free expression.

The wolves are celebrating their victory at the gate. Inside the farm, let’s be slightly more creative than shooting the penguin for pleasure.

Extra

This article at the The Hindu Business Line website

Credits: Book cover image by Gwydion M. Williams, CC BY 2.0, via Flickr

Copyright © 2014 The Hindu Business Line